Audio

THR History and Development

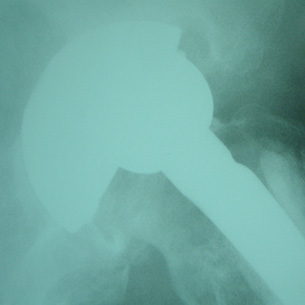

A hip without a hip joint! There is no ball to be seen. This was the end result of a failed total hip replacement. Infection was so bad and so established that the only choice was to take the hip replacement out and leave it out for a period. This is the so-called excision arthroplasty or Girdlestone procedure. Whether the patient would ever walk normally again was uncertain.

A failing total hip replacement. Look at how the ball (femoral head) of the artificial hip is lying eccentrically in the socket. This is because the polyethylene liner of the socket has become worn away and will need replacing.

A revision total hip replacement showing the socket area filled with allograft bone (the dense, white area) in order to reconstruct lost bone stock created by the original hip replacement which had been in place for many, many years.

It is a sad fact of life that nothing lasts forever. However well a primary hip replacement is performed, however modern the design, however good the hospital, hip replacements do eventually fail if left in place for sufficiently long. When failure occurs it is necessary for the operation to be redone, the so-called revision hip replacement. A commonly asked question is "How many times can it be done, doctor?" There is no definite answer to this, though the author has undertaken a nineteenth revision on one patient's hip. Do not rely on this for every case, however!

Revisions form an expanding part of modern orthopaedic surgery. Operations are more complex, they take longer (three hours would be a good average), equipment more comprehensive and expensive, and complications more frequent. In short, revisions are best avoided if possible. There are two categories of revision hip replacement:

- Revisions for infected loosening

- Revisions for uninfected loosening

Revisions for infected loosening

If infection strikes a hip replacement, simple antibiotic treatment is often insufficient to clear the condition. The only real way of eliminating the infection is to remove the artificial components. This is easier said than done. Frequently the components have been cemented in place, or bone has grown into them, making extraction extremely difficult and fraught with hazard. Nevertheless, the job must be done.

Special instruments can be used, such as ultrasonic cement removal systems, high speed cutters and burrs, and demanding techniques such as the transfemoral approach, where the femur bone is split to gain access to the component lying within. All man-made material must be removed, the entire area then being cleaned thoroughly, often with pulsatile lavage, a form of high-pressure water jet. Sometimes it is possible to reimplant a new hip at the same sitting, but quite often a surgeon will elect to leave the patient without a hip joint for a period, say three months, before returning to insert the new components. The period without a hip is used to treat any residual infection with antibiotics.

This two-stage revision is a widely accepted way of eliminating infection. Some advocate leaving the hip out for up to one year, but that is seen by many as being too long for a patient to withstand life without a hip joint. Three months is a reasonable compromise.

One-stage revisions are sometimes performed, especially if the bacterium responsible for the infection is not particularly virulent, or if the patient is medically unfit and thus unlikely to easily withstand a staged procedure. However, whatever treatment system is offered, it is difficult for any surgeon to guarantee that infection will not recur despite all best efforts. It is for this reason that all precautions are normally taken at the primary replacement to ensure infection does not gain access to the artificial hip in the first place - antibiotic therapy, ultraclean air flows within the operating theatre, antibiotic-impregnated bone cement, rigid aseptic technique, and so on.

Revisions for uninfected loosening

Even when infection is not a problem, revision surgery still represents an enormous challenge to both patient and surgeon. The biggest issue is the handling of bone stock loss. As a primary replacement begins to loosen, so the bone surrounding it begins to thin. Simply inserting a new component into the thin bone is one alternative, but the chances are that the revision operation will not last very long if that is done.

Reconstitution of bone stock is a major issue in modern orthopaedic surgery. The commonest way of handling the situation is with the use of bone allograft. This is bone retrieved from bone donors. Donors are traditionally patients undergoing primary hip replacement. When their arthritic femoral head is removed to make way for the artificial hip joint, the bone can be saved, morcellised, sterilised, and reinserted into another patient. Cadavers can also be a source of bone, with large tissue banks now set up to deal with the enormous demand worldwide for allograft bone. Great care must obviously be taken in donor selection, to ensure that disease is not transmitted from donor to recipient. Roughly the same guidelines that are applicable to blood donors also apply to bone donors.

Following allografting it is often necessary for a patient to remain non-weight bearing for a lengthy period; three months would be common. Non-weight bearing is hard work as no weight at all is allowed through the operated leg while the allograft incorporates into the patient. Even at the three-month point it may still be necessary to walk in a protected manner; quite often a limp is a permanent feature.

Revision surgery is a big, demanding area and not lightly undertaken. Its magnitude is one major reason why surgeons often try so hard to dissuade patients from undergoing the primary replacement in the first place. Orthopaedic surgeons know all too well what is involved with revision surgery - its perils and its pitfalls.