Audio

THR History and Development

For generations, surgeons have been faced with the problem of how to treat the painful hip. Replacement is only one of many different treatment options available. Alternatives do exist. Even though more than 500,000 hip replacements are performed worldwide every year, many of the alternatives are still used in special situations.

The problem with hip replacement is that it is irreversible. There is no going back once a damaged hip has been removed and an artificial one inserted. That is why surgeons frequently try and dissuade patients from having a hip replacement at all. However well a replacement is performed, however carefully it is looked after, and whatever design is used, it is difficult to make it last for ever. This is particularly true for the younger individual, say those aged under 50 years.

Alternatives to hip replacement were once performed in the days when artificial hips could not be safely implanted. Now, such alternatives are often used as holding procedures - operations that can be curative in their own right, but more likely simply delay the day when hip replacement may be required.

Although hip replacement is now widely undertaken, and many still regard it as a relatively new operation, it is not new at all! The first was performed by a Dr Gluck in 1891. Since then, many different types of replacement have been developed. For example, Professor Hey Groves, in 1926, reported the use of an ivory femoral head replacement that involved replacing the femoral head with half of an ivory sphere. Ivory is no longer used but the design does show how inventive surgeons have been in their attempts to provide relief for the painful hip. In these early days a hip replacement was not as we know it today. Now, most patients will receive what is called a total hip replacement, involving replacement of both acetabulum (hip socket) and femoral head (hip ball) by separate, artificial components, or prostheses.

The early designs were often femoral head replacements only, the acetabulum being left alone. This operation was known as hemiarthroplasty and is still widely used today in the management of hip fractures, particularly in the elderly. A more modern form of hemiarthroplasty, the bipolar hemiarthroplasty, has also been used occasionally in the management of the painful hip, particularly in the younger individual. The bipolar hemiarthroplasty had a socket already pre-attached to the femoral head before the artificial hip was inserted.

At about the same time as Hey Groves' ivory hip, attention was also being paid to the maintenance of sterile conditions during surgery, now known to be a vital part of any operation that involves the implantation of man-made materials into patients. Much of orthopaedic surgery, be it joint replacement, fracture fixation, or other lesser-known operations, involves the implantation of artificial materials. Strict sterility is thus essential.

Hip replacements continued to develop through the mid-1900s. The Judet brothers from France at one point proposed an acrylic design. Again, this did well in the short term, but failed relatively quickly by modern standards. It also had the reputation of squeaking whenever a patient walked! However, it was in the late 1950s that a major advance arrived with the use of bone cement. This was also an acrylic material, used by the dental profession at that time. It was John Charnley, an English surgeon, who suggested that acrylic bone cement (polymethylmethacrylate-PMMA) should be used to fix the artificial components to bone. Thus began the modern era of hip replacement surgery. Cement became widely used, certainly in the United Kingdom, and the results of replacement surgery improved enormously.

Not everyone agreed that hip replacements needed to be cemented to bone. In some parts of the world - the USA and Continental Europe are good examples - cementless fixation was used. Indeed, cementless designs are now widely used. Various techniques have been developed in order to encourage a patient's bone to grow into a cementless prosthesis, a process called osseointegration. In the early days it was a matter of drilling large holes through the stem of the femoral component (e.g. the Austin Moore prosthesis) in the hope that bone would grow through them. This did not always happen.

Next it was decided to roughen artificial components during manufacture, to encourage bone to grow into the microscopic irregularities such a roughening process created. The result was not always satisfactory. Roughening was then more liberally applied, in the form of small beads on the surface of the component. This is known as porous coating, still widely used today. As an alternative to porous coating, some manufacturers have coated their components with a special chemical - hydroxyapatite. Put simply, hydroxyapatite tricks the bone that the artificial component is a natural material so that bone grows into it, locking the component tightly in position.

A common combination of prostheses is to use a cemented femoral component but a cementless acetabular one. This is based on the theory that cemented femoral components do better than cementless ones. However, cemented acetabular components are seen by many as being the weak point in any hip replacement, so a cementless socket is thought to be a safer alternative. The combination of cementless and cemented fixation is known as hybrid fixation. Hybrid hips are widely undertaken and results are good.

A vital aspect of a hip replacement is the type of material used. Traditionally a replacement comprises a metal ball (stainless steel or cobalt chrome) and a plastic (high density polyethylene - HDPE) socket. This arrangement does well, but over many years of use minute particles of plastic can be set free - so called wear debris - and these, in turn, can cause bone destruction (osteolysis). This destruction causes loosening of the hip replacement. Much effort has thus been expended in finding a bearing surface that does not release more plastic than is necessary. Higher grade plastic has been invented that resists wear. This is sometimes referred to as highly cross-linked polyethylene. Ceramics have been introduced, and even a metal-on-metal articulation created, using a metal ball and a precisely engineered metal socket to match the ball. Essentially, these latter designs give a plastic-free hip so that the problem of polyethylene debris does not exist.

Whenever a surgeon undertakes a hip replacement operation, in the back of his or her mind is the worry that, one day, the replacement may have to be redone. This is revision surgery, a subspecialty that brings enormous challenges for both patient and surgeon. The success of a revision operation depends in large part on how much bone remains onto which a further hip replacement can be attached. The less bone that is removed at the original (or primary) replacement, the better the chance of a successful revision. For this reason some surgeons attempt to remove minute amounts of bone at the primary replacement by inserting a femoral component that has no stem to it at all. The component looks like a metal cap sitting directly on the ball of the femoral head. A metal liner is inserted into the acetabulum. This is resurfacing arthroplasty. Results for resurfacing arthroplasty have not always been good. That is why some surgeons do not believe in the operation. However, there is no doubt that certain centres can produce satisfactory results and in the late 1990s and early 2000s large numbers were performed throughout the world. However, a number of centres also reported an association between metal-on-metal articulations and early loosening, albeit in a very small number of patients. The spotlight is thus still on resurfacing and to whether or not it has a future.

For those patients who may not need a full total hip replacement with its long stem that passes down the femur, or for those for whom resurfacing arthroplasty is inappropriate, another version of hip arthroplasty exists. This is the so-called microplasty, or stubby stem hip replacement, or minihip. This has all the advantages of a full total hip replacement but without the long stem on the femoral component. The aim of the microplasty is to preserve femoral bone stock so that sufficient remains for any subsequent operations.

In addition, the microplasty is what is called “modular”. Modularity means that the components which are assembled to form a microplasty come separately at the time of surgery. The stem of the femoral component is separate to the ball, thereby allowing the surgeon to adjust sizes and materials right up to the last minute during an operation. Meanwhile the acetabular component comes in two parts, the shell on the outside and the liner on the inside, against which the ball will articulate. Again, the surgeon can adjust the size, shape and material from which the liner is made, in an attempt to achieve a more precise fit to the patient. This also has advantages at revision surgery as if a microplasty requires to be revised it is not usually the whole thing which must be changed. Often all that is required is a new ball, or perhaps a new liner. Modularity allows such an exchange to take place with generally much less trauma to the patient than a full revision operation. Modularity is also available to total hip replacement, so time will tell how well the microplasty performs. What is without doubt, however, is that hip replacement in all its forms has been a huge contribution to patients throughout the world. In quality of life terms, it is an operation that is very hard to beat.

|

|

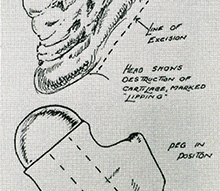

Drawing of Hey Groves’ ivory hip (circa 1926) |

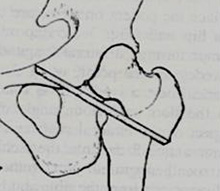

An alternative to total hip replacement, in the pre-replacement days, was this operation. This was known as an arthrodesis and involved fusing the hip surgically so that it never moved again. This was very good for pain relief but not very good for movement! The variety of arthrodesis shown here was known as Brittain’s extra-articular arthrodesis and was a particular favourite in the management of tuberculosis of the hip joint. |

|

|

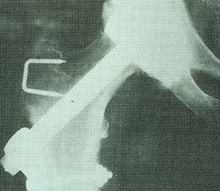

Another variety of hip arthrodesis (hip fusion) is shown here, circa 1954. Again, the aim was to fuse the hip so it could not move. On the extreme left of the drawing can be seen a piece of bone attached to a muscle pedicle. The aim of this was to ensure a good blood supply to the fused area so that healing could occur without delay or complication. |

An early variety of total hip replacement, the Wiles hip, circa 1936. Many of the original records of this hip replacement were destroyed in the London Blitz but by all accounts they did well. |

|

|

Another alternative to total hip replacement, an osteotomy. This involved division of the thigh bone in this case to create a surgical fracture. By shifting the lower part of the femur inwards, so the forces of walking were also directed inwards and could offload the damaged, osteoarthritic part of the hip. In some cases healing of the osteoarthritis occurred and in many cases pain was significantly reduced. This version of osteotomy was called a McMurray’s osteotomy. |

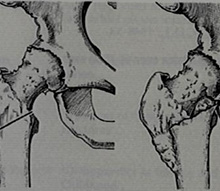

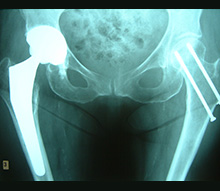

Two alternatives to total hip replacement are shown here. On the patient’s right (image’s left) the hip joint seems to have disappeared altogether! This is the so-called excision arthroplasty, or Girdlestone procedure, first introduced for the management of tuberculosis of the hip joint but now used as a final salvage procedure for a failed hip replacement. On the patient’s left (image’s right) can be seen a fused hip, or arthrodesis. Quite a pair of hips! |

|

|

An early variety of total hip replacement using a metal-on-metal articulation. This one lasted in this patient for more than 23 years! |

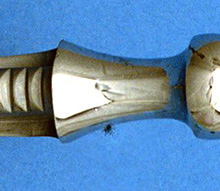

One of the original hip replacements pioneered by John Charnley in the United Kingdom. This was called a ‘cobra head’ prosthesis, for reasons which are obvious when the component is viewed from this angle. The component was fixed to the patient with bone cement. |

|

|

A component from an early cementless hip replacement, the Ring total hip. Note the polyethylene ball, which was rapidly replaced by newer designs with a metal ball. |

A photograph of a bipolar prosthesis. The large metallic dome is actually the hip socket, which is pre-attached to the ball of the component. The smaller ball cannot be seen as it lies within the large dome. This variety of bipolar component was called the Bateman bipolar prosthesis and was used for younger patients with osteoarthritis of the hip as well as older patients with a fractured neck of femur (hip fracture). |

|

|

The isoelastic prosthesis, which originated from Italy. Its purpose was to simulate the elasticity of the patient’s bone so that the hip replacement would last for a longer period than normal, particularly in the younger patient. This did not always prove to be the case. This prosthesis was also widely used for revision (redo) hip replacements because of its long stem and was inserted without bone cement. |

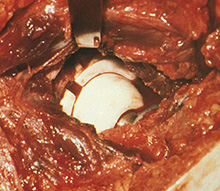

An operative view showing a more modern variety of total hip replacement, using a ceramic ball and a ceramic socket. The aim of using ceramic is to reduce the production of wear debris, which can be associated with a metal-on-polyethylene articulation. |

|

|

A modern variety of total hip replacement of a patient’s right hip (to the left of the photograph). On the other side may be seen two screws, previously inserted in order to fix a hip fracture. However, this hip replacement is cementless, the components being coated with hydroxyapatite in order to encourage bone ingrowth into the component. A fairly wide diameter of ball has been used on the femoral (thigh bone) component in order to reduce the chances of dislocation occurring after surgery. |