Audio

Surgery for Femoroacetabular Impingement

What Happens at Hip Arthroscopy?

Diagnostic round of the hip joint.

Arthroscopic excision of pincer impingement lesion

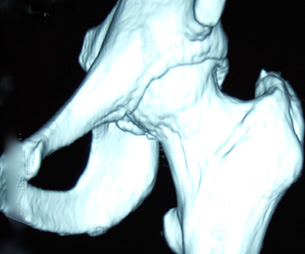

A three-dimensional CT scan showing a bump on the front of the hip ball. This is cam impingement.

The bump as seen through a hip arthroscope (keyhole viewing device). The bump can be removed by this means.

In the ideal world, a hip joint would comprise a perfectly spherical ball (femoral head) inside a perfectly matched socket (acetabulum). Unfortunately, for many of us, life is not like that. Sometimes from birth, sometimes as a result of changes during growth, or sometimes because of injury, disease, or even family history, the shape of the hip can become deformed. A bump can appear at the upper end of the thigh bone (femur), which slightly changes the shape of the ball. As the hip begins to bend, so the bump starts to catch, or impinge, on the front margin of the hip socket.

The same effect can occur even when the upper thigh bone is shaped normally but if the socket surrounds the ball more fully than usual, rather like a set of electrician’s pliers. This time, when the hip is bent, the thigh bone again impinges against the socket margins more easily. The first variety of impingement, when the ball has an abnormal shape, is called cam impingement, while the second variety is called pincer impingement. For many patients with impingement – or more properly, femoroacetabular impingement or FAI – both forms co-exist, the impingement then being referred to as mixed.

Typically, impingement will cause pain in the groin, particularly when the hip is bent (or flexed) to at least a right angle. This can occur when a patient is seated in a low chair, perhaps when driving a car, or in the bath. It can certainly interfere with sporting activities. Hurdling and rowing are both examples of sports which require full hip flexion and which FAI can significantly disrupt. However, any sport and a huge variety of normal daily activities can be compromised by this condition. Sometimes FAI can cause damage to the back of the hip joint as well as the front. This is because as the hip flexes, impingement eventually occurs at the front of the joint, which then begins to forcefully lever the ball backwards. This is called a ‘contrecoup’ effect and can explain why some patients feel pain at the back of the hip when the original cause is actually at the front.

The surgeon tests for FAI with a manoeuvre called the impingement test. For this, the patient is supine (face upwards) and their hip is bent to a right angle. The leg is then taken slightly across the midline (or adducted) and the hip is rotated inwards (or internal rotation). If this manoeuvre causes pain in the groin then the impingement test is described as being positive. It is a good indication that FAI is present and that there is damage to the hip joint.

In addition to a traditional examination, there are a number of investigations available which can help reinforce the diagnosis of FAI and assess the degree of impingement. These investigations can include simple X-Rays, plain MRI scanning, an MRI arthrogram (MRI scanning with a contrast dye), CT scanning and even three-dimensional CT scanning. Not every patient will need all of these investigations. Indeed, some patients will have just an examination and plain X-Ray, nothing more.

Hip joint damage caused by FAI can take a number of forms. At its simplest, the repeated bashing received by the margin of the hip socket from long-term FAI can damage a structure known as the labrum. This is attached to the margin of the socket and looks very like a knee cartilage. Its true function is still unknown but it probably helps maintain the vacuum seal within the hip joint and thus contributes to hip stability. If the labrum tears, the damage can extend to the gristle (articular cartilage) of the hip and eventually cause arthritis of the joint. This is one of the concerns about FAI, that it is a precursor of osteoarthritis (sometimes called osteoarthrosis). That said, not every hip with FAI will become osteoarthritic. Research has shown that this can happen in about two-thirds of cases.

The fact a hip has FAI does not always mean that surgery is necessary. The decision to operate will be based on many things but perhaps the most important is the disruption to life quality experienced by the patient. There is usually no harm in leaving the situation untouched for a period so that all parties involved can decide if surgery is the correct thing to do. This is because however good surgery may be, however good the surgical team, operations do not cure everyone

For the arthroscopic (keyhole) surgery technique, the chances of success, judged one year after surgery, are approximately 80%, with 15% of patients being no different and 5% being made worse. These figures must be balanced by the knowledge that FAI cannot improve without surgery, even if it is asymptomatic; there is a 100% certainty it will remain.

One factor that often makes a patient consider surgery is the worry that FAI can eventually become osteoarthritis. Although the link between the two conditions is clear, there is unfortunately no evidence that surgery can prevent this deterioration, much as one might wish to say otherwise. Consequently, when it comes to making the decision about surgery, this should be based on the degree of disruption to life quality at the time the FAI is identified, not on the basis of future worries.