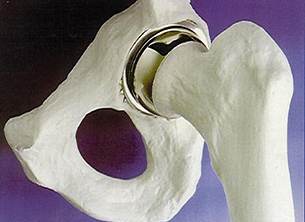

A full hip resurfacing. Note how the bulk of the bone of the upper femur has been preserved so that a total hip replacement may be performed if the resurfacing fails.

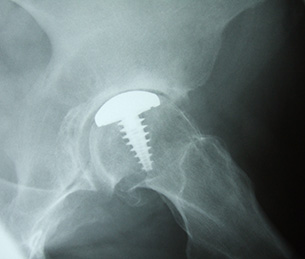

A partial hip resurfacing.

The concept of hip resurfacing is not new. The principle is very clear. If one can eliminate the pain of osteoarthritis without removing too much of a patient’s bone, then why not do so? With a total hip replacement, the femoral component (thigh bone component) normally has a lengthy stem which passes down the inside of the femur and secures the component to the bone. This works well but, when it comes to a revision hip replacement, the femur bone has already been used and may be too weak to accept a new femoral component. A resurfacing involves applying a cap to the femoral head (ball of the hip joint) and a liner to the inside of the acetabulum (socket of the hip joint). There have been plenty of attempts at resurfacing in earlier years, none of which worked particularly well. Indeed, one of the earliest designs was the ivory hip introduced by Professor Hey Groves in 1926. However, it was in the late 1970s and early 1980s that resurfacing emerged with a vengeance. On this occasion the design comprised a metal ball and a polyethylene socket. This combination did not do well. There were some reports of as many as 30% failing within three to four years of insertion. Understandably, resurfacing fell out of vogue for a period, although it was felt that the concept was a good one but that the materials used were the problem.

In the early 1990s resurfacing re-emerged, although this time a metal cap was used against a metal socket, a so-called metal-on-metal articulation. As one might imagine, the return of an operation which had previously failed so early in its history caused quite a stir in orthopaedic circles. However, the inventors stuck to their guns and it became clear towards the end of the 1990s that metal-on-metal hip resurfacing could do well, certainly much better than its metal-on-polyethylene ancestor. One huge attraction of a resurfacing is that to revise it to a total hip replacement is often a simple process, although sometimes this can be difficult.

Hip resurfacing has perhaps been studied more closely than any other hip operation. Whole meetings and huge symposia have taken place to discuss its place within the orthopaedic armamentarium. A number of concerns have been raised. These include fractures of the femoral neck (upper thigh bone) and the development of what have been called ‘pseudotumours’. These are not malignant tumours at all, so the term is somewhat misleading, but are evidence of a massive soft-tissue allergic reaction to the presence of metal. Fortunately such a finding is rare, less than 4 in 1000 cases, but when it happens it can be a significant problem which may demand early revision of the resurfacing to a total hip replacement.

Resurfacings can sometimes also be associated with muscle irritation around the hip joint, in particular a large muscle called iliopsoas. On occasion it is necessary to perform an arthroscopy (keyhole procedure) on a resurfacing in order to establish what may be going on within the joint, if pain is persistent after surgery.

It has also become clear that not all designs of resurfacing are the same. Some do well, some not so well. In addition, it is known that women do not fare as well as men after hip resurfacing and that those who require small sizes of components because of their smaller bone structure tend not to do as well as those who need larger sizes.

Despite all these findings, however, resurfacing is still an excellent choice of operation for many patients. Its design reduces the quantity of bone that is removed from a patient, thereby preserving it for later procedures, while its broad diameter significantly reduces the chance of a post-operative dislocation. With careful patient selection and, of course, careful surgical technique, hip resurfacing is still an excellent choice of operation for many individuals.

As well as a full hip resurfacing, which comprises a cap that totally covers the femoral head and a liner which covers the inner aspect of the hip socket, there is also a partial hip resurfacing available. This is a small stud-like insert which can be applied to localised areas of damage on the femoral head. For example ,a small area of avascular necrosis or an old area of injury. These partial hip resurfacings are excellent for specific, select conditions but do not appear to do particularly well as a treatment for osteoarthritis.